What Did Zhou Artisans Discover

The 4 occupations (simplified Chinese: 士农工商; traditional Chinese: 士農工商) or "4 categories of the people" (Chinese: 四民)[i] [2] was an occupation classification used in ancient People's republic of china past either Confucian or Legalist scholars every bit far back as the late Zhou dynasty and is considered a key part of the fengjian social structure (c. 1046–256 BC).[3] These were the shi (gentry scholars), the nong (peasant farmers), the gong (artisans and craftsmen), and the shang (merchants and traders).[three] The iv occupations were not always bundled in this society.[iv] [5] The four categories were non socioeconomic classes; wealth and standing did not stand for to these categories, nor were they hereditary.[one] [6]

The arrangement did not factor in all social groups nowadays in premodern Chinese lodge, and its broad categories were more an idealization than a practical reality. The commercialization of Chinese lodge in the Song and Ming periods further blurred the lines betwixt these four occupations. The definition of the identity of the shi class inverse over time—from warriors, to aristocratic scholars, and finally to scholar-bureaucrats. At that place was also a gradual fusion of the wealthy merchant and landholding gentry classes, culminating in the belatedly Ming Dynasty.

In some manner this system of social order was adopted throughout the Chinese cultural sphere. In Japanese information technology is called "Shi, nō, kō, shō" ( 士農工商 , shinōkōshō ), although in Japan information technology became a hereditary caste system.[7] [8] In Korean information technology is called "Sa, nong, gong, sang" (사농공상), and in Vietnamese is chosen "Sĩ, nông, công, thương (士農工商). The chief difference in adaptation was the definition of the shi (士).

Background [edit]

Street scene in Bianjing (modern Kaifeng)

From existing literary bear witness, commoner categories in China were employed for the first time during the Warring States period (403–221 BC).[9] Despite this, Eastern-Han (Advertizement 25–220) historian Ban Gu (Advertizing 32–92) asserted in his Book of Han that the four occupations for commoners had existed in the Western Zhou (c. 1050–771 BC) era, which he considered a golden age.[9] Nonetheless, information technology is at present known that the nomenclature of four occupations as Ban Gu understood it did not exist until the 2d century BC.[9] Ban explained the social hierarchy of each group in descending gild:

Scholars, farmers, artisans, and merchants; each of the four peoples had their respective profession. Those who studied in order to occupy positions of rank were called the shi (scholars). Those who cultivated the soil and propagated grains were chosen nong (farmers). Those who manifested skill (qiao) and made utensils were chosen gong (artisans). Those who transported valuable articles and sold commodities were chosen shang (merchants).[10]

The Rites of Zhou described the four groups in a different order, with merchants before farmers.[11] The Han-era text Guliang Zhuan placed merchants second later scholars,[iv] and the Warring States-era Xunzi placed farmers before scholars.[5] The Shuo Yuan mentioned a quotation which stressed the ideal of equality between the four occupations.[12]

Anthony J. Barbieri-Low, Professor of Early Chinese History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, writes that the classification of "four occupations" can be viewed as a mere rhetorical device that had no effect on government policy.[ix] However, he notes that although no statute in the Qin or Han constabulary codes specifically mentions the four occupations, some laws did treat these broadly classified social groups as separate units with different levels of legal privilege.[nine]

The categorisation was sorted co-ordinate to the principle of economic usefulness to state and society, that those who used listen rather than muscle (scholars) were placed get-go, with farmers, seen as the primary creators of wealth, placed next, followed by artisans, and finally merchants who were seen as a social disturbance for excessive accumulation of wealth or erratic fluctuation of prices.[13] Beneath the four occupations were the "hateful people" (Chinese: 賤民 jiànmín), outcasts from "humilitating" occupations such equally entertainers and prostitutes.[xiv]

The iv occupations were non a hereditary system.[1] [6] The four occupations organization differed from those of European bullwork in that people were not born into the specific classes, such that, for example, a son born to a gong craftsman was able to get a part of the shang merchant class, and so on. Theoretically, whatsoever homo could become an official through the Imperial examinations.[14]

From the fourth century BC, the shi and some wealthy merchants wore long flowing silken robes, while the working class wore trousers.[15]

Shī (士) [edit]

Ancient Warrior class [edit]

Chariot archer, c. 300 BC

During the ancient Shang (1600–1046 BC) and Early Zhou dynasties (1046–771 BC), the shi were regarded as a knightly social lodge of depression-level aristocratic lineage compared to dukes and marquises.[16] This social class was distinguished past their right to ride in chariots and command battles from mobile chariots, while they also served civil functions.[sixteen] Initially rising to power through controlling the new technology of bronzeworking, from 1300 BC, the shi transitioned from human foot knights to being primarily chariot archers, fighting with composite recurved bow, a double-edged sword known as the jian, and armour.[17]

The shi had a strict code of chivalry. In the battle of Zheqiu, 420 BC, the shi Hua Bao shot at and missed some other shi Gongzi Cheng, and just as he was nigh to shoot again, Gongzi Cheng said that it was unchivalrous to shoot twice without allowing him to return a shot. Hua Bao lowered his bow and was afterwards shot dead.[17] [18] In 624 B.C. a disgraced shi from the State of Jin led a suicidal charge of chariots to redeem his reputation, turning the tide of the battle.[17] In the Battle of Bi, 597 BC, the routing chariot forces of Jin were bogged down in mud, merely pursuing enemy troops stopped to help them get dislodged and allowed them to escape.[19]

As chariot warfare became eclipsed by mounted cavalry and infantry units with effective crossbowmen in the Warring States period (403–221 BC), the participation of the shi in boxing dwindled equally rulers sought men with actual military machine grooming, not but aristocratic background.[20] This was also a period where philosophical schools flourished in Red china, while intellectual pursuits became highly valued amid statesmen.[21] Thus, the shi somewhen became renowned not for their warrior's skills, but for their scholarship, abilities in administration, and audio ethics and morality supported past competing philosophical schools.[22]

Scholar-Officials [edit]

A Literary Garden, by Zhou Wenju, tenth century.

Under Duke Xiao of Qin and the master minister and reformer Shang Yang (d. 338 BC), the ancient State of Qin was transformed by a new meritocratic yet harsh philosophy of Legalism. This philosophy stressed stern punishments for those who disobeyed the publicly known laws while rewarding those who labored for the state and strove diligently to obey the laws. It was a means to diminish the ability of the nobility, and was another force behind the transformation of the shi class from warrior-aristocrats into merit-driven officials. When the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) unified China under the Legalist arrangement, the emperor assigned administration to dedicated officials rather than nobility, ending feudalism in Red china, replacing it with a centralized, bureaucratic government. The form of government created by the first emperor and his advisors was used by later dynasties to construction their ain government.[23] [24] [25] Under this organization, the government thrived, equally talented individuals could exist more easily identified in the transformed society. Notwithstanding, the Qin became infamous for its oppressive measures, and and so collapsed into a country of ceremonious war afterward the expiry of the Emperor.

Candidates gathering around the wall where the results are posted. This annunciation was known every bit "releasing the curl" (放榜). (c. 1540, by Qiu Ying)

The victor of this war was Liu Bang, who initiated four centuries of unification of Communist china proper nether the Han dynasty (202 BC–AD 220). In 165 BC, Emperor Wen introduced the commencement method of recruitment to ceremonious service through examinations, while Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BC), cemented the ideology of Confucius into mainstream governance installed a arrangement of recommendation and nomination in authorities service known equally xiaolian, and a national academy[26] [27] [28] whereby officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of the Confucian classics, from which Emperor Wu would select officials.[29]

In the Sui dynasty (581–618) and the subsequent Tang dynasty (618–907) the shi class would begin to present itself by means of the fully standardized civil service examination system, of partial recruitment of those who passed standard exams and earned an official degree. Yet recruitment past recommendations to role was still prominent in both dynasties. Information technology was not until the Song dynasty (960–1279) that the recruitment of those who passed the exams and earned degrees was given greater emphasis and significantly expanded.[30] The shi class also became less aristocratic and more bureaucratic due to the highly competitive nature of the exams during the Song period.[31]

Beyond serving in the administration and the judiciary, scholar-officials also provided regime-funded social services, such every bit prefectural or county schools, costless-of-charge public hospitals, retirement homes and paupers' graveyards.[32] [33] [34] Scholars such every bit Shen Kuo (1031–1095) and Su Vocal (1020–1101) dabbled in every known field of scientific discipline, mathematics, music and statecraft,[35] while others similar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) or Zeng Gong (1019–1083) pioneered ideas in early on epigraphy, archeology and philology.[36] [37]

A Chinese School (1847)[38]

From the 11th to 13th centuries, the number of exam candidates participating in taking the exams increased dramatically from only 30,000 to 400,000 by the dynasty's end.[39] Widespread printing through woodblock and movable type enhanced the spread of knowledge amongst the literate in society, enabling more people to become candidates and competitors vying for a prestigious degree.[31] [twoscore] With a dramatically expanding population matching a growing amount of gentry, while the number of official posts remained constant, the graduates who were not appointed to regime would provide critical services in local communities, such as funding public works, running private schools, aiding in revenue enhancement drove, maintaining order, or writing local gazetteers.[41] [42] [43] [44]

Nóng (农/農) [edit]

A farmer (nong) operating a pulley wheel to lift a saucepan, from the Tiangong Kaiwu encyclopedia by Vocal Yingxing (1587–1666)

Since Neolithic times in China, agriculture was a primal chemical element to the rise of China's civilization and every other culture. The food that farmers produced sustained the whole of order, while the land tax exacted on farmers' lots and landholders' belongings produced much of the land revenue for Cathay's pre-modern ruling dynasties. Therefore, the farmer was a valuable member of club, and even though he was not considered one with the shi grade, the families of the shi were commonly landholders that oftentimes produced crops and foodstuffs.[45]

Between the ninth century BC (late Western Zhou dynasty) to around the finish of the Warring States catamenia, agricultural land was distributed co-ordinate to the Well-field organization (井田), whereby a square surface area of land was divided into nine identically-sized sections; the eight outer sections (私田; sītián) were privately cultivated past farmers and the center section (公田; gōngtián) was communally cultivated on behalf of the landowning aristocrat. When the organisation became economically untenable in the Warring States period, it was replaced by a system of private land ownership. It was first suspended in the land of Qin by Shang Yang and other states soon followed accommodate.[46]

From AD 485–763, land was equally distributed to farmers under the Equal-field arrangement (均田).[47] [48] [49] Families were issued plots of land on the footing of how many able men, including slaves, they had; a woman would exist entitled to a smaller plot. As government control weakened in the 8th century, land reverted into the hands of private owners.

Vocal Dynasty (950–1279) rural farmers engaged in the small-calibration production of wine, charcoal, paper, textiles, and other goods.[50]

Past the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the socioeconomic course of farmers grew more than and more than indistinct from another social course in the four occupations: the artisan. Artisans began working on farms in meridian periods and farmers oft traveled into the city to notice work during times of famine.[51] The distinction between what was boondocks and state was blurred in Ming China, since suburban areas with farms were located only outside and in some cases within the walls of a city.[51]

Gōng (工) [edit]

Ming era pottery workshop

Artisans and craftsmen—their class identified with the Chinese graphic symbol meaning labour—were much like farmers in the respect that they produced essential goods needed by themselves and the rest of society. Although they could non provide the country with much of its revenues since they frequently had no country of their own to be taxed, artisans and craftsmen were theoretically respected more than than merchants. Since ancient times, the skilled work of artisans and craftsmen was handed downwards orally from begetter to son, although the work of architects and structural builders were sometimes codification, illustrated, and categorized in Chinese written works.[52]

Artisans and craftsmen were either government-employed or worked privately. A successful and highly skilled artisan could oftentimes gain enough capital in order to hire others as apprentices or additional laborers that could be overseen by the chief artisan as a manager. Hence, artisans could create their own small-scale enterprises in selling their work and that of others, and like the merchants, they formed their own guilds.[52]

Researchers have pointed to the rise of wage labour in late Ming and early Qing workshops in textile, paper and other industries,[53] [54] achieving large-scale production past using many small workshops, each with a small team of workers nether a main craftsman.[53]

Although architects and builders were not as highly venerated every bit the scholar-officials, there were some architectural engineers who gained wide acclaim for their achievements. I case of this would be the Yingzao Fashi printed in 1103, an architectural building manual written past Li Jie (1065–1110), sponsored by Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1126) for these regime agencies to utilize and was widely printed for the benefit of literate craftsmen and artisans nationwide.[55] [56]

Workers in the porcelain and silk industries (early 18th century)

In the late of Ming dynasty there were many porcelain kilns created that led the Ming dynasty to be economically well off.[57] The Qing emperors like the Kangxi Emperor helped the growth of porcelain export and by allowing an arrangement of private maritime trade that assisted families who owned private kilns.[58] Chinese export porcelain, designed purely for the European marketplace and unpopular amidst locals equally it lacked the symbolic significance of wares produced for the Chinese home market,[59] [lx] was a highly popular trade proficient.[61]

In Red china, silk-worm farming was originally restricted to women, and many women were employed in the silk-making industry.[62] Even every bit noesis of silk production spread to the rest of the earth, Song dynasty China was able to maintain near-monopoly on industry by large scale industrialization, through the two-person draw loom, commercialized mulberry tillage, and a factory production.[63] The organisation of silk weaving in 18th-century Chinese cities was compared with the putting-out system used in European textile industries between the 13th and 18th centuries. Equally the interregional silk trade grew, merchant houses began to organize manufacture to guarantee their supplies, providing silk to households for weaving as piece work.[64]

Shāng (商) [edit]

Delineation of a marketplace, Han dynasty

In Ancient pre-Regal China, merchants were highly regarded as necessary for the circulation of essential goods. The legendary Emperor Shun, prior to receiving the throne from his predecessor, was said to be a merchant. Archaeological artifacts and oracle bones suggest a loftier status was accorded to merchant activity. In the Spring and Autumn Menses, Hegemon of China Duke Huan of Qi appointed Guan Zhong, a merchant, equally Prime Minister. He cut taxes for merchants, built rest stops for merchants, and encouraged other lords to lower tariffs.[11]

In Imperial Mainland china, the merchants, traders, and peddlers of goods were viewed by the scholarly elite as essential members of guild, yet were esteemed least of the four occupations in club, due to the view that they were a threat to social harmony from acquiring disproportionally large incomes,[13] marketplace manipulation or exploiting farmers.[65]

However, the merchant grade of Communist china throughout all of Chinese history were usually wealthy and held considerable influence above its supposed social standing.[66] The Confucian philosopher Xunzi encouraged economical cooperation and substitution. The distinction between gentry and merchants was not as clear or entrenched equally in Japan and Europe, and merchants were even welcomed by gentry if they abided by Confucian moral duties. Merchants accustomed and promoted Confucian order by funding education and charities, and advocating Confucian values of cocky-tillage of integrity, frugality, and hard work. Past the belatedly imperial catamenia, information technology was a trend in some regions for scholars to switch to careers as merchants. William Rowe'southward research of rural elites in late imperial Hanyang, Hubei shows that there was a very high level of overlap and mixing between the gentry and the merchants.[67]

Han Dynasty writers mention merchants owning huge tracts of land.[68] A merchant who owned property worth a thousand catties of gold—equivalent to ten million cash coins—was considered a great merchant.[69] Such a fortune was i hundred times larger than the boilerplate income of a heart class landowner-cultivator and dwarfed the annual 200,000 cash-money income of a marquess who collected taxes from a thousand households.[70] Some merchant families fabricated fortunes worth over a hundred million cash, which was equivalent to the wealth acquired by the highest officials in authorities.[71] Afoot merchants who traded between a network of towns and cities were often rich every bit they had the power to avoid registering as merchants (unlike the shopkeepers),[72] Chao Cuo (d. 154 BC) states that they wore fine silks, rode in carriages pulled by fat horses, and whose wealth allowed them to associate with authorities officials.[73]

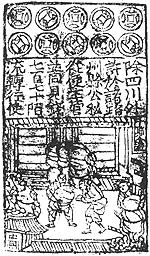

The commencement banknotes originated in China as merchant receipts in the 7th century, becoming regime-issued currency by the 11th century.[74] [75] [76] [77]

Historians similar Yu Yingshi and Billy So have shown that as Chinese society became increasingly commercialized from the Song dynasty onward, Confucianism had gradually begun to accept and even support business concern and trade as legitimate and viable professions, as long as merchants stayed abroad from unethical deportment. Merchants in the meantime had also benefited from and utilized Confucian ideals in their concern practices. By the Song period, merchants oft colluded with the scholarly elite; every bit early as 955, the Scholar-officials themselves were using intermediary agents to participate in trading.[66] Since the Vocal regime took over several fundamental industries and imposed strict state monopolies, the regime itself acted as a large commercial enterprise run by scholar-officials.[78] The land besides had to argue with the merchant guilds; whenever the country requisitioned goods and assessed taxes it dealt with gild heads, who ensured fair prices and fair wages via official intermediaries.[79] [80]

Painting of a woman and children surrounding a peddler of goods in the countryside, by Li Song (c. 1190–1225), dated 1210 Advertising

By the late Ming Dynasty, the officials often needed to solicit funds from powerful merchants to build new roads, schools, bridges, pagodas, or engage in essential industries, such as book-making, which aided the gentry class in education for the imperial examinations.[81] Merchants began to imitate the highly cultivated nature and manners of scholar-officials in society to appear more cultured and gain college prestige and acceptance by the scholarly elite.[82] They even purchased printed books that served as guides to proper acquit and behavior and which promoted merchant morality and business ethics.[83] The social condition of merchants rose to such significance[84] [85] [86] that by the belatedly Ming period, many scholar-officials were unabashed to declare publicly in their official family histories that they had family members who were merchants.[87] The scholar-officials' dependence upon merchants received semi-legal standing when scholar-official Qiu Jun (1420–1495), argued that the state should only mitigate market affairs during times of pending crisis and that merchants were the best gauge in determining the strength of a nation's riches in resource.[88] The Imperial court followed this guideline by granting merchants licenses to trade in salt in return for grain shipments to borderland garrisons in the north.[89] The country realized that merchants could buy common salt licenses with silver and in turn boost state revenues to the point where buying grain was not an issue.[89]

Merchants banded in organisations known as huiguan or gongsuo; pooling capital was popular as it distributed risk and eased the barriers to market place entry. They formed partnerships known as huoji zhi (silent investor and active partner), lianhao zhi (subsidiary companies), jingli fuzhe zhi (possessor delegates control to a manager), xuetu zhi (apprenticeship), and hegu zhi (shareholding). Merchants had a tendency to invest their profits in vast swathes of land.[90] [91]

Exterior Prc [edit]

Outside of China, the same values permeated and prevailed across other Eastward Asian societies where China exerted considerable influence. Japan and Korea were heavily influenced by Confucian thought that the four occupational social hierarchy in those societies were modeled from that of China'south.[92]

Ryukyu Kingdom [edit]

A like state of affairs occurred in the Ryūkyū Kingdom with the scholarly class of yukatchu, but yukatchu status was hereditary and could be bought from the government as the kingdom'due south finances were frequently scarce.[93] Due to the growth of this class and the lack of government positions open for them, Sai On allowed yukatchu to become merchants and artisans while keeping their high status.[94] At that place were three classes of yukatchu, the pechin, satonushi and chikudun, and commoners may exist admitted for meritorious service.[95] The Ryukyu Kingdom's capital of Shuri also featured a university and school system, alongside a civil service test system.[96] The government was managed by the Seissei, Sanshikan and the Bugyo (Prime Government minister, Council of Ministers and Administrative Departments). Yukatchu who failed the examinations or were otherwise accounted unsuitable for office would be transferred to obscure posts and their descendants would fade into insignificance.[97] Ryukyuan students were too enrolled into the National Academy (Guozijian) in Prc, at Chinese government expense, and others studied privately at schools in Fujian province such diverse skills as law, agronomics, calendrical calculation, medicine, astronomy, and metallurgy.[98]

Japan [edit]

In Japan, the Four Occupations was modified into a rigid hereditary iv-caste system,[99] where marriage across caste lines was socially unacceptable.[seven] In Japan, the Scholar role was taken by the hereditary samurai class. Originally a martial class, the samurai became civil administrators to their daimyōs during the Tokugawa shogunate. No exams were needed as the positions were inherited. They constituted almost 5% of the population and were allowed to have a proper surname. (run into Edo lodge).[7]

In the sixteenth century, lords began to centralise administration past replacing enfeoffment with stipend grants, and placing pressure on vassals to relocate into castle towns, away from independent power bases. Military commanders became rotated to avoid the formation of stiff personal loyalties from the troops. Artisans and merchants were solicited by these lords and sometimes received official appointments. This century was a catamenia of exceptional social mobility, with instances of merchants of samurai-descent or commoners condign samurai. By the eighteenth century samurai and merchants had go interwoven intimately, despite general samurai hostility toward merchants who every bit their creditors were blamed for the financial difficulties of a debt-ridden samurai class.[100]

Korea [edit]

Korean envoys to the United states

In Silla Korea, the scholar-officials, also known as Head rank 6, v, and iv (두품), were strictly hereditary castes nether the Bone rank system (골품제도), and their power was express by the Royal clan who monopolized the positions of importance.[101]

From the late 8th century, succession wars in Silla, equally well as frequent peasant uprisings, led to the dismantling of the bone-rank system. Head rank 6 leaders sojourned to China for report, while regional governance fell into the hojok or castle-lords commanding private armies detached from the central regime. These factions coalesced, introducing a new national ideology that was an affiliation of Chan Buddhism, Confucianism and Feng Shui, laying the foundation for the germination of the new Goryeo Kingdom. King Gwangjong of Goryeo introduced a ceremonious service exam system in 958, and Rex Seongjong of Goryeo complemented it with the institution of a Confucian-style educational facilities and administration structures, extending for the showtime time to local areas. However, only aristocrats were permitted to sit for these examinations, and the sons of officials of at least 5th rank were exempt completely.[102]

In Joseon Korea, the Scholar occupation took the form of the noble yangban class, which prevented the lower classes from taking the advanced gwageo exams and then they could dominate the bureaucracy. Below the yangban were the chungin, a course of privileged commoners who were piffling bureaucrats, scribes, and specialists. The chungin were actually the least populous class, even smaller than the yangban. The yangban constituted 10% of the population.[103] From the mid-Joseon period, war machine officers and civil officials were separately derived from different clans.[104]

Vietnam [edit]

Vietnamese Mandarins in the 19th century

Vietnamese dynasties also adopted the examination degree system (khoa-cử) to recruit scholars for authorities service.[105] [106] [107] [108] [109] The bureaucrats were similarly divided into nine grades and 6 ministries, and examinations were held annually at provincial level, and triennially at regional and national levels.[110] The Vietnamese political aristocracy consisted of educated landholders whose interests often clashed with the central government. Although all land theoretically was the ruler'south, and was supposed to be distributed equitably by the Equal-field organisation (khau phan dien che) and non-transferable, the courtroom hierarchy increasingly appropriated land which they leased to tenant farmers and hired labourers to till.[111] It was unlikely for individuals of common background to become Mandarins, however, since they lacked admission to classical education. Degree-holders were ofttimes clustered in certain clans.[112]

Maritime Southeast Asia [edit]

Tjong Ah Fie, a Chinese officer in the Dutch East Indies

Chinese official positions, under various different native titles, go dorsum to the courts of precolonial states of Southeast Asia, such as the Sultanates of Malacca and Banten, and the Kingdom of Siam. With the consolidation of colonial rule, these became office of the civil hierarchy in Portuguese, Dutch and British colonies, exercising both executive and judicial powers over local Chinese communities under the colonial government,[113] [114] [115] examples being the title of Chao Praya Chodeuk Rajasrethi in Thailand's Chakri Dynasty,[116] and Sri Indra Perkasa Wijaya Bakti, the Malay courtroom position of Kapitan Cina Yap Ah Loy, arguably the founder of modern Kuala Lumpur.[117]

Overseas Chinese merchant families in British Malaya and the Dutch Indies donated generously to the provision of defence and disaster relief programs in Cathay in club to receive nominations to the Imperial Court for honorary official ranks. These ranged from chün-hsiu, a candidate for the Imperial examinations, to chih-fu (Chinese: 知府; pinyin: zhīfŭ ) or tao-t'ai (Chinese: 道臺; pinyin: dàotái ), prefect and circuit intendant respectively. The bulk of these sinecure purchases were at the level of t'ungchih (Chinese: 同知; pinyin: tóngzhī ), or sub-prefect, and below. Garbing themselves in the official robes of their rank in about ceremonial functions, these wealthy dignitaries would adopt the conduct of scholar-officials. Chinese language newspapers would list them exclusively equally such and precedence at social functions would be determined past title.[118]

In colonial Indonesia, the Dutch government appointed Chinese officers, who held the ranks of Majoor, Kapitein or Luitenant der Chinezen with legal and political jurisdiction over the colony's Chinese subjects.[119] The officers were overwhelmingly recruited from erstwhile families of the 'Cabang Atas' or the Chinese gentry of colonial Indonesia.[120] Although appointed without state examinations, the Chinese officers emulated the scholar-officials of Imperial China, and were traditionally seen locally as upholders of the Confucian social order and peaceful coexistence under the Dutch colonial authorities.[119] For much of its history, date to the Chinese officership was determined past family background, social standing and wealth, but in the twentieth century, attempts were fabricated to elevate meritorious individuals to high rank in keeping with the colonial government'south and then-called Ethical Policy.[119]

The merchant and labour partnerships of China adult into the Kongsi Federations across Southeast Asia, which were associations of Chinese settlers governed through direct commonwealth.[121] On Borneo they established sovereign states, the Kongsi republics such as the Lanfang Democracy, which bitterly resisted Dutch colonisation in the Kongsi Wars.[122]

Unclassified occupations [edit]

The renowned Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649); the emperor represented the pinnacle of traditional Chinese society, and was above that of the scholar-official.

There were many social groups that were excluded from the four broad categories in the social hierarchy. These included soldiers and guards, religious clergy and diviners, eunuchs and concubines, entertainers and courtiers, domestic servants and slaves, prostitutes, and low class laborers other than farmers and artisans. People who performed such tasks that were considered either worthless or "filthy" were placed in the category of mean people (賤人), non being registered equally commoners and having some legal disabilities.[1]

Imperial clan [edit]

The emperor—embodying a heavenly mandate to judicial and executive authority—was on a social and legal tier above the gentry and the test-drafted scholar-officials. Under the principle of the Mandate of Heaven, the correct to rule was based on "virtue"; if a ruler was overthrown, this was interpreted as an indication that the ruler was unworthy, and had lost the mandate, and at that place would often be revolts post-obit major disasters as citizens saw these as signs that the Mandate of Heaven had been withdrawn.[123] The Mandate of Heaven does not require noble birth, depending instead on just and able performance. The Han and Ming dynasties were founded past men of common origins.[124] [125]

Although his royal family and noble extended family were also highly respected, they did non command the same level of authority.

During the initial and end phases of the Han dynasty, the Western Jin Dynasty, and the Northern and Southern dynasties, the members of the Royal clan were enfeoffed with vassal states, decision-making military and political ability: they frequently usurped the throne, intervened in Imperial succession, or fought ceremonious wars.[126] From the 8th century on, the Tang dynasty purple clan was restricted to the capital and denied fiefdoms, and by the Song dynasty were also denied any political power. By the Southern Vocal dynasty, purple princes were assimilated into the scholars, and had to take the regal examinations to serve in government, like commoners. The Yuan dynasty favoured the Mongol tradition of distributing Khanates, and under this influence, the Ming dynasty also revived the do of granting titular "kingdoms" to Imperial clan members, although they were denied political command;[127] only near the end of the dynasty were some permitted to partake in the examinations to qualify for government service as common scholars.[128]

Eunuchs [edit]

Imperial court conference, Ming dynasty

The court eunuchs who served the royals were also viewed with some suspicion past the scholar-officials, since there were several instances in Chinese history where influential eunuchs came to dominate the emperor, his imperial court, and the whole of the central authorities. In an extreme case, the eunuch Wei Zhongxian (1568–1627) had his critics from the orthodox Confucian 'Donglin Society' tortured and killed while dominating the court of the Tianqi Emperor—Wei was dismissed by the adjacent ruler and committed suicide.[129] In pop culture texts such as Zhang Yingyu'due south The Book of Swindles (ca. 1617), eunuchs were often portrayed in starkly negative terms as enriching themselves through excessive taxation and indulging in cannibalism and debauched sexual practices.[130] The eunuchs at the Forbidden City during the later Qing period were infamous for their abuse, stealing every bit much every bit they could.[131] The position of eunuch at the Forbidden City offered such opportunities for theft and corruption that countless men willingly become eunuchs in order to live a better life.[131] Ray Huang argues that eunuchs represented the personal volition of the Emperor, while the officials represented the alternate political will of the bureaucracy. The clash betwixt them would thus have been a clash of ideologies or political calendar.[132]

Religious workers [edit]

Luohan Laundering, Buddhist artwork of five luohan and ane bellboy, past Lin Tinggui, 1178 AD

Although shamans and diviners in Bronze Age Cathay had some authority equally religious leaders in society, as authorities officials during the early Zhou dynasty,[133] with the Shang dynasty Kings sometimes described as shamans,[134] [135] and may have been the original physicians, providing elixirs to care for patients,[136] e'er since Emperor Wu of Han established Confucianism every bit the state religion, the ruling classes have shown increasing prejudice against shamanism,[137] preventing them from amassing likewise much power and influence like military strongmen (i example of this would exist Zhang Jiao, who led a Taoist sect into open rebellion confronting the Han government'due south authority[138]).

Fortune-tellers such equally geomancers and astrologers were non highly regarded.[139]

Buddhist monkhood grew immensely popular from the fourth century, where the monastic life's exemption from tax proved attracting to poor farmers. 4,000 government-funded monasteries were established and maintained through the medieval menstruum, eventually leading to multiple persecutions of Buddhism in China, a lot of the contention being over Buddhist monasteries' exemption from government revenue enhancement,[140] only also because later Neo-Confucian scholars saw Buddhism as an alien credo and threat to the moral guild of lodge.[141]

However from the fourth to twentieth centuries, Buddhist monks were frequently sponsored by the elite of order, sometimes even by Confucian scholars, with monasteries described as "in size and magnificence no prince's firm could match".[142] Despite the strong Buddhist sympathies of the Sui Dynasty and Tang dynasty rulers, the curriculum of the Imperial Examinations was nevertheless defined by Confucian catechism as information technology alone covered political and legal policy necessary to regime.[143]

War machine [edit]

Ming Dynasty troops in formation

The social category of the soldier was left out of the social bureaucracy due to the gentry scholars' embracing of intellectual cultivation (文 wén) and detest for violence (武 wǔ).[144] The scholars did not desire to legitimize those whose professions centered chiefly around violence, and so to leave them out of the social hierarchy altogether was a means to keep them in an unrecognized and undistinguished social tier.[144]

Soldiers were not highly respected members of society,[45] specifically from the Song dynasty onward, due to the newly instituted policy of "Emphasizing the civil and downgrading the military" (Chinese: 重文輕武).[145] Soldiers traditionally came from farming families, while some were simply debtors who fled their land (whether owned or rented) to escape lawsuits past creditors or imprisonment for failing to pay taxes.[45] Peasants were encouraged to join militias such as the Baojia (保甲) or Tuanlian (團練),[146] but full-time soldiers were commonly hired from amnestied bandits or vagabonds, and peasant militia were mostly regarded as the more than reliable.[144] [147] [148]

From the 2nd century B.C. onward, soldiers forth Cathay's frontiers were besides encouraged by the state to settle downward on their own subcontract lots in order for the food supply of the military to become self-sufficient, under the Tuntian system (屯田),[149] the Weisuo system (衛所) and the Fubing system (府兵).[150] [151] Nether these schemes, multiple dynasties attempted to create a hereditary war machine caste past exchanging edge farmland or other privileges for service. Nevertheless, in every instance, the policy would fail due to rampant desertion caused by the extremely low regard for violent occupations, and subsequently these armies had to replaced with hired mercenaries or even peasant militia.[144] [152]

Han Dynasty Han Xin rose from destitution to political ability through military success

However, for those without formal teaching, the quickest way to power and the upper echelons of society was to join the armed services.[153] [154] Although the soldier was looked upon with a flake of disdain by scholar-officials and cultured people, military officers with successful careers could gain a considerable amount of prestige.[155] Despite the claim of moral loftier ground, scholar-officials oft commanded troops and wielded military power.[144]

Entertainers [edit]

Entertaining was considered to exist of piddling use to society and was usually performed by the underclass known every bit the "mean people" (Chinese: 賤民).[14]

Entertainers and courtiers were often dependents upon the wealthy or were associated with the often-perceived immoral pleasance grounds of urban entertainment districts.[156] Musicians who played music as full-time work were of depression status.[157] To give them official recognition would have given them more prestige.

"Proper" music was considered a primal aspect of nurturing of character and good government, but vernacular music, equally defined as having "irregular movements" was criticised as corrupting for listeners. In spite of this, Chinese society idolized many musicians, even women musicians (who were seen as seductive) such as Cai Yan (ca. 177) and Wang Zhaojun (40-30 B.C).[158] Musical abilities were a prime consideration in marriage desirability.[159] During the Ming dynasty, female musicians were so mutual that they fifty-fifty played for imperial rituals.[159]

Private theatre troupes in the homes of wealthy families were a common practice.[159]

Professional dancers of the flow were of low social condition and many entered the profession through poverty, although some such as Zhao Feiyan achieved college condition by becoming concubines. Some other dancer was Wang Wengxu (王翁須) who was forced to go a domestic vocalist-dancer but who later on bore the future Emperor Xuan of Han.[160] [161]

Institutions were set up to oversee the training and performances of music and dances in the majestic court, such as the Neat Music Bureau (太樂署) and the Drums and Pipes Agency (鼓吹署) responsible for formalism music.[162] Emperor Gaozu set up the Regal Academy, while Emperor Xuanzong established the Pear Garden University for the grooming of musicians, dancers and actors.[163] At that place were around 30,000 musicians and dancers at the regal court during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong,[164] with most specialising in yanyue. All were nether the administration of the Drums and Pipes Bureau and an umbrella system chosen the Taichang Temple (太常寺).[165]

Professional artists had similarly low status.[139]

Slaves [edit]

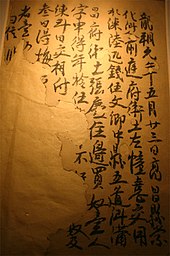

Contract for the purchase of a slave, Tang dynasty Xinjiang

Slavery was comparatively uncommon in Chinese history only was yet good, largely as a judicial punishment for crimes.[166] [167] [168] In the Han and Tang dynasties, it was illegal to trade in Chinese slaves (that were not criminals), but foreign slaves were adequate.[169] [170] The Xin dynasty emperor Wang Mang, the Ming dynasty Hongwu emperor, and Qing dynasty Yongzheng emperor attempted to ban slavery entirely but were not successful.[168] [171] [172] Illegal enslavement of children oftentimes occurred nether the guise of adoption from poor families.[169] It has been speculated past researchers such as Sue Gronewold that up to 80% of late Qing era prostitutes may have been slaves.[173]

Vi dynasties, Tang dynasty, and to a partial extent Song dynasty society also contained a complex system of servile groups included under "mean people" (賤人) that formed intermediate standings betwixt the four occupations and outright slavery. These were, in descending order:[xiv]

- the musicians of the Imperial Sacrifices 太常音聲人

- general bondsmen 雑戶, including Imperial tomb guards

- musician households 樂戶

- official bondsmen 官戶

- government slaves 奴婢

And in private service,

- personal retainers 部曲

- female retainers 客女

- private slaves 家奴

These performed a wide assortment of jobs in households, in agronomics, delivering letters or as private guards.[14]

See also [edit]

- Social structure of China

- Edo society

- Estates of the realm

- Club and culture of the Han dynasty

- Social club of the Song dynasty

- Yangban, Chungin, Sangmin and Cheonmin in Korea

- Youxia

- Kheshig

- Samurai

- Hwarang

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d Hansson, pp. 20-21

- ^ Brook, 72.

- ^ a b Fairbank, 108.

- ^ a b (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

古者有四民:有士民,有商民、有農民、有工民。夫甲,非人人之所能為也。丘作甲,非正也。

- ^ a b (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

農農、士士、工工、商商

- ^ a b Byres, Terence; Mukhia, Harbans (1985). Feudalism and Non European Societies. London: Frank Cass and Co. pp. 213, 214. ISBN0-7146-3245-seven.

- ^ a b c George De Vos and Hiroshi Wagatsuma (1966). Japan'due south invisible race: caste in culture and personality . Academy of California Printing. ISBN978-0-520-00306-4.

- ^ Toby Slade (2009). Japanese Mode: A Cultural History. Berg. ISBN978-1-84788-252-3.

- ^ a b c d eastward Barbieri-Depression (2007), 37.

- ^ Barbieri-Low (2007), 36–37.

- ^ a b Tang, Lixing (2017). "1". Merchants and Society in Modernistic Prc: Rise of Merchant Groups China Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN978-1351612999.

- ^ (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

春秋曰:四民均則王道興而百姓寧;所謂四民者,士、農、工、商也。

- ^ a b Kuhn, Philip A. (1984). Chinese views of social classification, in James L. Watson, Class and Social stratification in postal service-Revolution Prc. Cambridge University Press. pp. twenty–21. ISBN0521143845.

- ^ a b c d e Hansson, 28-xxx

- ^ Gernet, 129–130.

- ^ a b Ebrey (2006), 22.

- ^ a b c Peers, pp. 17, 20, 24, 31

- ^ . (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

將注豹.則關矣.曰.平公之靈.尚輔相余.豹射出其間.將注.則又關矣.曰.不狎鄙.抽矢.城射之.殪.張匄抽殳而下.射之.折股.扶伏而擊之.折軫.又射之.死.

- ^ (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

晉人或以廣隊.不能進.楚人惎之脫扃.少進.馬還.又惎之拔旆投衡.乃出

- ^ Ebrey (2006), 29–xxx.

- ^ Ebrey (2006), 32.

- ^ Ebrey (2006), 32–39.

- ^ "China'due south First Empire | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Globe and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia, p. 36

- ^ Borthwick 2006, pp. 9–ten

- ^ Michael Loewe 1994 p.. Divination, Mythology and Monarchy in Han China. https://books.google.com/books?id=m2tmgvB8zisC

- ^ Creel, H.G. (1949). Confucius: The Man and the Myth. New York: John Day Company. pp. 239–241

- Creel, H.G. 1960. pp. 239–241. Confucius and the Chinese Way

- Creel, H.G. 1970, What Is Taoism?, 86–87

- Xinzhong Yao 2003. p. 231. The Encyclopedia of Confucianism: 2-volume Set. https://books.google.com/books?id=P-c4CQAAQBAJ&pg=PA231

- Griet Vankeerberghen 2001 pp. 20, 173. The Huainanzi and Liu An's Merits to Moral Authority. https://books.google.com/books?id=zt-vBqHQzpQC&pg=PA20

- ^ Michael Loewe pp. 145, 148. 2011. Dong Zhongshu, a 'Confucian' Heritage and the Chunqiu Fanlu. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZQjJxvkY-34C&pg=PA145

- ^ Edward A Kracke Jr, Civil Service in Early Sung People's republic of china, 960-1067, p 253

- ^ Ebrey (1999), 145–146.

- ^ a b Ebrey (2006), 159.

- ^ Gernet, 172.

- ^ Ebrey et al., Eastern asia, 167.

- ^ Yuan, 193–199.

- ^ Ebrey et al., East asia, 162–163.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 148.

- ^ Fraser & Haber, 227.

- ^ "A Chinese School". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. 4: 108. October 1847. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- ^ Ebrey (2006), 160.

- ^ Fairbank, 94.

- ^ Fairbank, 104.

- ^ Fairbank, 101–106.

- ^ Michael, 420–421.

- ^ Hymes, 132–133.

- ^ a b c Gernet, 102–103.

- ^ Zhufu, Fu (1981), "The economic history of Red china: Some special problems", Modern China, vii (ane): seven, doi:10.1177/009770048100700101, S2CID 220738994

- ^ Charles Holcombe (2001). The Genesis of East asia: 221 B.C. – A.D. 907. Academy of Hawaii Press. pp. 136–. ISBN978-0-8248-2465-5.

- ^ David Graff (2003). Medieval Chinese Warfare 300–900. Routledge. pp. 140–. ISBN978-i-134-55353-2.

- ^ Dr R K Sahay (2016). History of Red china's Military. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. pp. 103–. ISBN978-93-86019-ninety-5.

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 141.

- ^ a b Spence, xiii.

- ^ a b Gernet, 88–94

- ^ a b Faure, David (2006), China and commercialism: a history of business concern enterprise in modern Prc, Agreement Cathay: New Viewpoints on History And Culture, Hong Kong University Press, pp. 17–eighteen, ISBN978-962-209-784-1

- ^ Rowe, William T. (1978–2020). "Social stability and social change". In Fairbank, John Grand.; Twitchett, Denis (eds.). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 526.

- ^ Needham, Book 4, Role three, 84.

- ^ Guo, 4–6.

- ^ Medley, Margaret (1987). "The Ming – Qing Transition in Chinese Porcelain". Arts Asiatiques. 42: 65–76. doi:10.3406/arasi.1987.1217. JSTOR 43486524.

- ^ Zhao, Gang (2013). The Qing Opening to the Ocean: Chinese Maritime Policies, 1684–1757. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 116–136.

- ^ Newton, Bettina (2014). "xiv". Beginner's Guide To Antique Collection. Karan Kerry. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Burton, William (1906). "The Letters of Père D'Entrecolles". Porcelain: its nature art and industry. London: B. T. Batsford Ldt. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Valenstein, Susan K. (1989). A handbook of Chinese ceramics. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 197. ISBN0-87099-514-6.

- ^ Federico, Giovanni (1997). An Economic History of the Silk Industry, 1830–1930. Cambridge university Press. pp. 14, xx. ISBN0521581982.

- ^ Heleanor B. Feltham: Justinian and the International Silk Trade, p. 34

- ^ Li, Lillian M. (1981), Communist china'southward silk trade: traditional industry in the modern earth, 1842–1937, Harvard East Asian monographs, vol. 97, Harvard Univ Asia Heart, pp. 50–52, ISBN978-0-674-11962-eight

- ^ (in Chinese) – via Wikisource.

其商工之民,修治苦窳之器,聚弗靡之財,蓄積待時,而侔農夫之利。

- ^ a b Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in Cathay on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated past H.M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0 pp. 68–69

- ^ Guo Wu (2010). Zheng Guanying: Merchant Reformer of Late Qing Prc and His Influence on Economics, Politics, and Social club. Cambria Press. pp. xiv–16. ISBN978-1604977059.

- ^ Ch'ü (1969), 113–114.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), 114.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), 114–115.

- ^ Ch'u (1972), 115–117.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), 576.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), 576–577; Ch'ü (1972), 114; see also Hucker (1975), 187.

- ^ Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais (2006), 156.

- ^ Bowman (2000), 105.

- ^ Peter Bernholz (2003). Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 53. ISBN978-one-84376-155-6.

- ^ Daniel R. Headrick (one April 2009). Technology: A Globe History. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN978-0-nineteen-988759-0.

- ^ Gernet, 77.

- ^ Gernet, 88.

- ^ Ebrey et al., E Asia, 157.

- ^ Beck, 90–93, 129–130, 151.

- ^ Brook, 128–129, 134–138.

- ^ Brook, 215–216.

- ^ Yu Yingshi 余英時, Zhongguo Jinshi Zongjiao Lunli yu Shangren Jingshen 中國近世宗教倫理與商人精神. (Taipei: Lianjing Chuban Shiye Gongsi, 1987).

- ^ Baton And then, Prosperity, Region, and Institutions in Maritime China. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 253–279.

- ^ Billy So, "Institutions in market economies of premodern maritime China." In Billy So ed., The Economy of Lower Yangzi Delta in Tardily Imperial China. (New York: Routledge, 2013), 208–232.

- ^ Beck, 161

- ^ Brook, 102.

- ^ a b Brook, 108.

- ^ Tang, Lixing (2017). "2". Merchants and Society in Modernistic Cathay: Rising of Merchant Groups China Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN978-1351612999.

- ^ Fang Liufang; Xia Yuantao; Sang Binxue; Danian Zhang (1989). "Chinese Partnership". Constabulary and Gimmicky Problems: The Emerging Framework of Chinese Civil Constabulary: [Function 2]. 52 (iii).

- ^ Ho, Kwon Ping; De Meyer, Arnoud (2017). The Art of Leadership: Perspectives from Distinguished Thought Leaders. World Scientific Publishing. ISBN978-9813233485.

- ^ Smits, 73.

- ^ Steben, 47.

- ^ Kerr, George H. (2011). Okinawan: The History of an Island People. Tuttle. ISBN978-1462901845.

- ^ Smits, Gregory (1999). Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modern Thought and Politics. University of Hawaii Press. p. 14. ISBN0824820371.

- ^ Kerr, George H. (1953). Ryukyu Kingdom and Province Before 1945 (Scientific investigations in the Ryukyu Islands). National Academies.

- ^ Smits, Gregory (1999). Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early-Modernistic Thought and Politics. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN0824820371.

- ^ David L. Howell (2005). Geographies of identity in nineteenth-century Japan. University of California Printing. ISBN0-520-24085-v.

- ^ Totman, Conrad (1981). Nippon Before Perry: A Brusque History (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. pp. 139–140, 161–163. ISBN0520041348.

- ^ Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN0-674-61576-10.

- ^ 신형식 (2005). "1-two". A Brief History of Korea, Volume one A Brief History of Korea Book 1 of The spirit of Korean cultural roots Volume 1 of Uri munhwa ŭi ppuri rŭl chʻajasŏ (illustrated, reprint ed.). Ewha Womans Academy Printing. ISBN8973006193.

- ^ Nahm, Andrew C (1996). Korea: Tradition and Transformation — A History of the Korean People (second ed.). Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International. pp. 100–102. ISBN1-56591-070-2.

- ^ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 165–167. ISBN9780742567177.

- ^ John Kleinen Facing the Futurity, Reviving the Past: A Study of Social Change in ... – 1999 – Page 71

- ^ Truong Buu Lâm, New lamps for former: the transformation of the Vietnamese ... -Found of Southeast Asian Studies – 1982 Page 11- "The provincial examinations consisted of three to four parts which tested the following areas: knowledge of the Confucian texts... The title of cu nhan or "person presented" (for part) was conferred on those who succeeded in all four tests."

- ^ D. W. Sloper, Thạc Cán Lê Higher Instruction in Vietnam: Modify and Response – 1995 Page 45 " For those successful in the court competitive examination 4 titles were awarded: trang nguyen, being the first- rank doctorate and first laureate, blindside nhan, being a first-rank doctorate and 2d laureate; tham hoa, being a first-rank ..."

- ^ Nguyẽn Khá̆c Kham , Yunesuko Higashi An introduction to Vietnamese culture Ajia Bunka Kenkyū Sentā (Tokyo, Japan) 1967 – Folio xx "The classification became more elaborate in 1247 with the Tam-khoi which divided the first category into 3 separate classes: Trang-nguyen (first prize winner in the competitive examination at the rex'south courtroom), Bang-nhan (second prize ..."

- ^ Walter H. Slote, George A. De Vos Confucianism & the Family 998 – Page 97 "1428–33) and his collaborators, especially Nguyen Trai (1380–1442) — who was himself a Confucianist — accustomed ... of Trang Nguyen (Zhuang Yuan, or first laureate of the national examination with the highest recognition in every copy)."

- ^ SarDesai, D R (2012). "2". Southeast Asia: By and Nowadays (7 reprint ed.). Hachette Uk. ISBN978-0813348384.

- ^ John Kleinen Facing the Future, Reviving the Past: A Study of Social Alter in ... – 1999 – Folio 5, 31-32

- ^ Woodside, Alexander; American Quango of Learned Societies (1988). Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Regime in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century ACLS Humanities East-Book Volume 140 of E Asian Monograph Series Harvard East Asian monographs, ISSN 0073-0483 Volume 52 of Harvard East Asian series History e-book project (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Harvard Univ Asia Eye. p. 216. ISBN067493721X.

- ^ Ooi, Keat Gin. Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, From Angkor Wat to Democratic republic of timor-leste, p. 711

- ^ Hwang, In-Won. Personalized Politics: The Malaysian Country Under Matahtir, p. 56

- ^ Buxbaum, David C.; Clan of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning (2013). Family unit Constabulary and Customary Law in Asia: A Contemporary Legal Perspective. Springer. ISBN9789401762168 . Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "The Siamese Aristocracy". Soravij . Retrieved 9 Jan 2017.

- ^ Malhi, PhD., Ranjit Singh (May 5, 2017). "The history of Kuala Lumpur's founding is non equally clear cutting as some call up". www.thestar.com.my. The Star. The Star Online. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ Godley, Michael R. (2002). The Mandarin-Capitalists from Nanyang: Overseas Chinese Enterprise in the Modernisation of Red china 1893-1911 Cambridge Studies in Chinese H Cambridge Studies in Chinese History, Literature and Institutions. Cambridge Academy Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN0521526957.

- ^ a b c Lohanda, Mona (1996). The Kapitan Cina of Batavia, 1837-1942: A History of Chinese Establishment in Colonial Society. Jakarta: Djambatan. ISBN9789794282571 . Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Haryono, Steve (2017). Perkawinan Strategis: Hubungan Keluarga Antara Opsir-opsir Tionghoa Dan 'Cabang Atas' Di Jawa Pada Abad Ke-19 Dan 20. Steve Haryono. ISBN9789090302492 . Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Wang, Tai Peng (1979). "The Word "Kongsi": A Note". Journal of the Malaysian Co-operative of the Majestic Asiatic Order. 52 (235): 102–105. JSTOR 41492844.

- ^ Heidhues, Mary Somers (2003). Golddiggers, Farmers, and Traders in the "Chinese Districts" of West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN978-0-87727-733-0.

- ^ Szczepanski, Kallie. "What Is the Mandate of Heaven in China?". About Educational activity . Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ "Gaozu Emperor of Han Dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Mote, Frederick Due west.; Twitchett, Denis, eds. (1988). The Cambridge History of Cathay, Volume 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN978-0-521-24332-two.

- ^ Wang, R.G., p. 20

- ^ Wang, R.G. p. xxi

- ^ Wang, R.M. p. 10

- ^ Spence, 17–18.

- ^ Zhang Yingyu, The Book of Swindles: Selections from a Late Ming Drove, translated by Christopher Rea and Bruce Rusk (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

- ^ a b Behr, Edward The Terminal Emperor London: Futura, 1987 folio 73.

- ^ Huang, Ray (1981). 1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline . New Oasis: Yale University Printing. ISBN0-300-02518-1.

- ^ Von Falkenhausen, Lothar (1995). Reflections of the Political Role of Spirit Mediums in Early on China: The Wu Officials in the Zhou Li, volume twenty. Guild for the study of Early China. pp. 282, 285.

- ^ Chang, Kwang-Chih (1983). Fine art, Myth, and Ritual: The Path to Political Potency in Ancient China. Harvard University Press. pp. 45–47.

- ^ Chen, Mengjia (1936). 商代的神話與巫術 [Myths and Magic of the Shang Dynasty]. Yanjing xuebao 燕京學報. p. 535. ISBN9787101112139.

- ^ Schiffeler, John Wm. (1976). "The Origin of Chinese Folk Medicine". Asian Folklore Studies. Asian Folklore Studies 35.1. 35 (2): 27. doi:10.2307/1177648. JSTOR 1177648. PMID 11614235.

- ^ Groot, January Jakob Maria (1892–1910). The Religious Arrangement of China: Its Aboriginal Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Continued Therewith. Brill Publishers. pp. 1233–1242.

- ^ de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A biographical dictionary of Later Han to the Iii Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Brill. p. 1058. ISBN978-90-04-15605-0.

- ^ a b Hui chen, Wang Liu (1959). The Traditional Chinese Clan Rules. Association for Asian Studies. pp. 160–163.

- ^ Gernet, Jacques. Verellen, Franciscus. Buddhism in Chinese Club. 1998. pp. 14, 318-319

- ^ Wright, 88–94.

- ^ Brook, Timothy (1993). Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China. Harvard University Printing. pp. 2–3. ISBN0674697758.

- ^ Wright, 86

- ^ a b c d e Fairbank, 109.

- ^ Peers, p. 128

- ^ Peers, pp. 114, 130

- ^ Peers, pp. 128-130,180,199

- ^ Swope, Kenneth One thousand. (2009). The Armed services Plummet of China'south Ming dynasty. Routledge. p. 21.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. "Tuntian". People's republic of china knowledge.

- ^ Liu, Zhaoxiang; et al. (2000). History of Military Legal System. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House. ISBNvii-5000-6303-2.

- ^ Peers, pp. 110-112

- ^ Peers, pp. 175-179

- ^ Lorge, 43.

- ^ Ebrey et al., Eastern asia, 166.

- ^ Graff, 25–26

- ^ Jones, Andrew F. (2001). Yellowish Music: Media Civilization and Colonial Modernity in the Chinese Jazz Age . Duke Academy Printing. p. 29. ISBN0822326949.

the social condition of professional musicians china.

- ^ Nettl, Bruno; Rommen, Timothy (2016). Excursions in Globe Music. Taylor & Francis. p. 131. ISBN978-1317213758.

- ^ Ko, Dorothy; Kim, JaHyun; Pigott, Joan R. (2003). Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern China, Korea, and Japan. University of california press. pp. 112–114. ISBN0520231384.

- ^ a b c Ko, Dorothy; Kim, JaHyun; Pigott, Joan R. (2003). Women and Confucian Cultures in Premodern Mainland china, Korea, and Japan. University of california press. pp. 97–99. ISBN0520231384.

- ^ Selina O'Grady (2012). And Human being Created God: Kings, Cults and Conquests at the Time of Jesus. Atlantic Books. p. 142. ISBN978-1843546962.

- ^ "《趙飛燕別傳》". Chinese Text Projection. Original text: 趙後腰骨纖細,善踽步而行,若人手持花枝,顫顫然,他人莫可學也。

- ^ Sharron Gu (2011). A Cultural History of the Chinese Language. McFarland. pp. 24–25. ISBN978-0786466498.

- ^ Tan Ye (2008). Historical Lexicon of Chinese Theater. Scarecrow Press. p. 223. ISBN978-0810855144.

- ^ Dillon, Michael (24 Feb 1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Routledge. pp. 224–225. ISBN978-0700704392.

- ^ China: Five Thousand Years of History and Civilization. Urban center University of Hong Kong Press. 2007. pp. 458–460. ISBN978-9629371401.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, inc (2003). The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 27. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 289. ISBN0-85229-961-3 . Retrieved 2011-01-eleven .

- ^ The Get-go Emperor of China by Li Yu-Ning(1975)

- ^ a b Hallet, Nicole. "Prc and Antislavery". Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolitionism, Vol. 1, p. 154 – 156. Greenwood Publishing Grouping, 2007. ISBN 0-313-33143-Ten.

- ^ a b Hansson, p. 35

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (1963), The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Written report of T'ang Exotics, University of California Press, pp. 44–45

- ^ Encyclopedia of Antislavery and Abolitionism. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. 2011. p. 155. ISBN978-0-313-33143-5.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, p. 420, at Google Books

- ^ Gronewold, Sue (1982). Beautiful merchandise: Prostitution in China, 1860-1936. Women and History. pp. 12–thirteen, 32.

References [edit]

- Barbieri-Depression, Anthony J. (2007). Artisans in Early Regal Prc. Seattle & London: Academy of Washington Printing. ISBN 0-295-98713-viii.

- Brook, Timothy. (1998). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming People's republic of china. Berkeley: Academy of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22154-0

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, Anne Walthall, James Palais. (2006). Eastern asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Visitor. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- __________. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman (1992). Cathay: A New History; 2d Enlarged Edition (2006). Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Printing. ISBN 0-674-01828-1

- Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250–1276. Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0

- Michael, Franz. "State and Social club in Nineteenth-Century China", Globe Politics: A Quarterly Journal of International Relations (Volume iii, Number 3, April 1955): 419–433.

- Smits, Gregory (1999). "Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early on-Modern Thought and Politics". Honolulu: Academy of Hawai'i Printing.

- Spence, Jonathan D. (1999). The Search For Mod Prc; 2d Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Visitor. ISBN 0-393-97351-four (Paperback).

- Steben, Barry D. "The Manual of Neo-Confucianism to the Ryukyu (Liuqiu) Islands and its Historical Significance".

- Wright, Arthur F. (1959). Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Yuan, Zheng. "Local Government Schools in Sung Red china: A Reassessment", History of Didactics Quarterly (Volume 34, Number 2; Summer 1994): 193–213.

- Lorge, Peter (2005). War, Politics and Society in Early on Modern China, 900–1795: 1st Edition. New York: Routledge.

- Wang, Richard Thousand. (2008), "The Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Aristocracy" OUP Usa, ISBN 0199767688

- Peers, C.J., Soldiers of the Dragon, Osprey, New York ISBN 1-84603-098-six

- Hansson, Anders, Chinese Outcasts: Discrimination and Emancipation in Belatedly Imperial Prc 1996, BRILL ISBN 9004105964

What Did Zhou Artisans Discover,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_occupations

Posted by: kirbytherstaid.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Did Zhou Artisans Discover"

Post a Comment